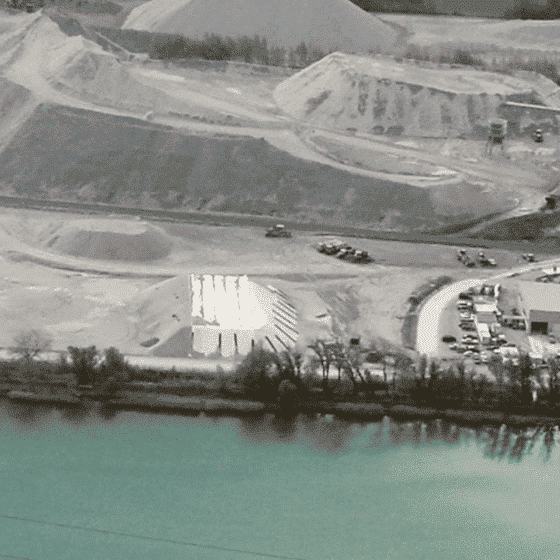

Smart Cities: improvement of urban governance and quality of life for inhabitants

What is behind the concept of Smart City, which appeared in the early 2000s? What do we mean by “Smart”? What role does technology play in this system? What are the issues? Anne-Laure Morard, who co-manages BG’s Smart City Division, sheds light on the topic.

Saturated traffic, lack of parking spaces, water shortage during scorching summers, pollution, health crisis. Here These are some of the increasingly numerous and complex challenges facing cities around the world today. To cope, governments and citizens can rely on digital technologies. BG therefore created the Smart City Division almost two years ago to respond to these challenges: “This is a cross-disciplinary organisation that is developing a Smart City strategy. The know-how cultivated there is made available to municipalities, but also to regions, departments, cantons and industrial operators in order to meet the needs of the population and the challenges of sustainability. Concretely, we support them in becoming Smart Cities. In particular, we help them to identify the specific needs of different players and, to prioritise the actions to be implemented with the appropriate solutions using technology. The objective is twofold: to increase the quality of life of the population and improve urban governance,” explains Anne-Laure Morard, co-head of the division and project manager.

According to her vision, there is no ready-made recipe for cities wishing to embrace a Smart City concept. “When developing a strategy, we must take into account the specific expectations of citizens, the needs of communities and businesses, as well as the geographical typology. For example, a mountain municipality will need a service allowing real-time road snow removal, while in a rural environment we will put more emphasis on mobility issues for people without means of transport. This could notably lead to the establishment of a vehicle sharing system.” “There are as many Smart Cities as there are territories,” adds the project manager.

Smart Cities therefore take different forms, but the use of technology is recurrent. “Through information systems and other innovative means, we manage to spare resources and deliver services more efficiently.” To illustrate her point, the engineer puts forward the hypervisor solution. “It is a visualisation tool that allows various information, such as data from different departments in a city, to be superimposed on a single map. Which can be very useful. Let’s assume that a power failure occurs and its cause is unknown. You would only have to connect to the system to realise that the damaged cable passes near a water pipe being renovated”. Such a system therefore provides an overview, which improves crisis management, with a direct impact on the service provided to the user. The project manager emphasises that achieving this is more complicated than it seems, since it requires a cross-functional approach. “This way of working is not natural for public entities, which are generally organised in silos,” specifies Anne Laure Morard.

Municipalities are not the only ones to have to step out of their comfort zone. For BG, organisational evolution began almost three years ago. “Generally, engineers are specialised in a field of activity, such as mobility, energy, building or water management. The implementation of Smart City strategies requires skills in all these areas, as well as an overview. Fortunately, BG has a rich DNA through the diversity of its know-how and its profiles. Skills that we have brought together for several years within the Smart City Division,” she concludes.

(Article taken from BG Magazine 2021, updated version on the site)